Give women the choice to have more babies

If fertility rates don’t rise, the UK faces economic stagnation or vastly higher levels of immigration

MIRIAM CATES6 November 2023 • 7:00am

Storks aren't delivering: Falling birth rates are endangering our prosperity – yet 92 per cent of young women in the UK want at some stage to be mothers

After a post-war baby boom,

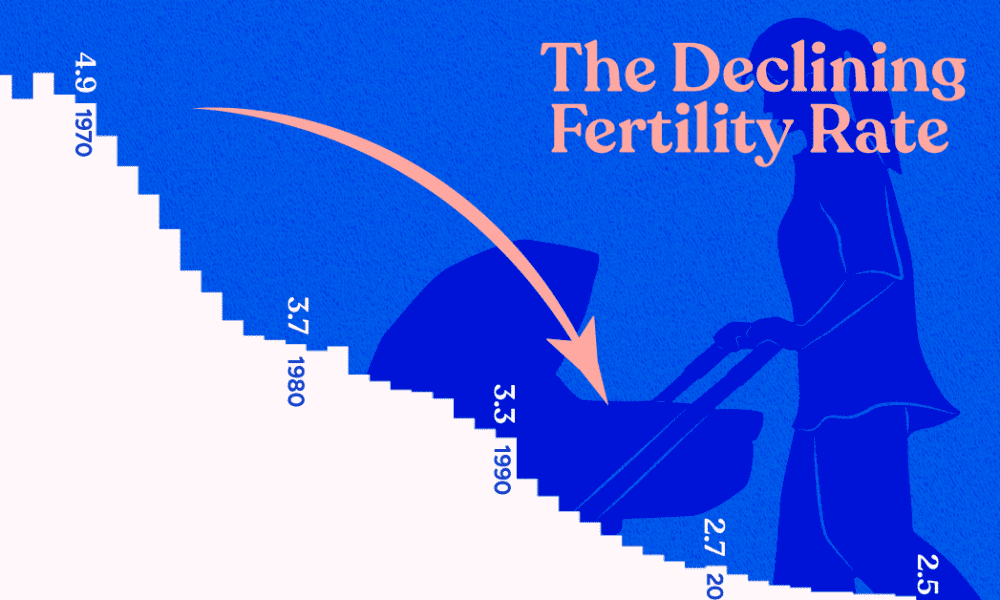

Britain now faces a baby bust. The UK fertility rate fell to a low of just 1.56 children per woman, well under the oft-cited 2.1 needed for demographic stability. As a result, since the 1970s the ratio of working age people to pensioners has dropped from four-to-one to three-to-one. It continues to fall.

The

economic consequences of this shift are mind blowing. If you think that in 2023 taxes are too high and care workers too scarce, you have seen nothing yet. A paper released last week by demographer Paul Morland and economist Philip Pilkington shows that to avoid this economic catastrophe we would have to accept such extraordinarily high levels of immigration that by 2080 40 per cent of the UK population would not have been born here.

Alternatively we must resign ourselves to economic stagnation, permanent inflation and a crisis in elderly care. Unless, of course, we increase the birthrate.

Few in Britain are talking about these issues. That’s why today I am hosting a Centre for Social Justice discussion in Parliament to raise awareness amongst MPs, journalists and policy makers about the need to take declining birthrates seriously. We also need to start proposing solutions.

The good news is that

the shortage of babies is not due to lack of demand. Exclusive polling commissioned for today’s event shows that

92 per cent of young women want children and that the average number of children desired is 2.4. In other words, if women were able to have the number of children they actually wanted, we wouldn’t have a problem.

But whilst the desire is there, sadly it often goes unfulfilled. Only a tiny minority of the young women in our poll said they don’t want children, yet on current trends one in three will likely never become mothers.

This represents a deep personal tragedy for many. Policy makers must seek, as far as possible, to remove the barriers that prevent those who want to have children from doing so.

Our polling gives some indications about where to begin. The most common factor cited for delaying starting a family is the impact on household finances. Although it will take considerable political will to address this, generous tax breaks for families and a radical approach to housing would be a start.

Half of young women cited career impact as a reason for delaying children. Legislators and employers should create guarantees for mothers to return to their career at the same level following a break.

Although economic factors are clearly important and must be addressed, this is not the whole answer. Many Western countries have cheaper housing, better family tax policies and even universal free childcare –

but still have lower fertility rates than the UK.

Perhaps the most significant finding of our poll was that

nearly three quarters of young women feel society doesn’t value motherhood enough. Our culture too often paints motherhood as drudgery rather than celebrating the incomparable fulfilment that so many women find in bearing and nurturing children.

We must value mothers more. But we also need to teach young people the facts about female fertility. Seventy-eight per cent of those surveyed believe there should be better fertility education in school. A surprising result of the poll was that most young women believe waiting until age 35 is not too late to start a family and that fertility treatments make conception possible at any age.

Whilst celebrities having children later in life – and through IVF – fill popular culture,

the sad truth of declining fertility is that whilst the chance of a woman in her 20s conceiving is 25 per cent each month, this drops to under 5 per cent at age 40. And IVF over 40 has a success rate of just one in 10. For too many women, delaying motherhood means never becoming a mother at all.

So what is to be done? Reducing economic barriers to family formation is difficult but essential. Improving fertility education is within our grasp. But culture change will be far harder to achieve. It is incumbent on those in public life to start talking about children as a blessing, rather than a burden on parents or the economy. But the important first step is to recognise that fertility-rate decline is a serious problem that needs creative solutions.