Given your background, and as well read as you are, I suspect that this book will not be a revelation to you. On the other hand it is a new discovery to me.

Clode, 1869 "The Military Forces of the Crown"

play.google.com

Two quotes stuck out for me.

And

Which leads to this

en.wikipedia.org

bcw-project.org

And to this

All of which, in my mind puts the 2004 ruling as yet one more power play in a discussion that is more than 800 years old, predating the Edward I's Statutes of Westminster of 1285.

The Crown's Lieutenants, be they Lords-Lieutenant, Lieutenants Governor or Governors are by history, law and tradition the agents of the Crown and are responsible for the maintenance of Peace, Order and Good Governance, as we have it in Canada. The Crown is advised by the Executive Council, now democratically elected, but it is the Crown that holds the authority. That authority includes the right to administer justice and to call out the entire male community, between the ages of 15 and 60 to support the Crown.

That body, by 1641, had come to be known as a militia. And by 1869, two years after Confederation, while British Law was still the controlling law in Canada, Clode was comfortable stating, unequivocally, "

The Constitutional Force for the Defence of the realın is the Militia".

That position was the accepted position, even in Canada, until the innovations of the 1940s and the establishment of the Sedentary, Non-Permanent Active, and Permanent Active Militias as the Canadian Army (Regular) and the Canadian Army (Reserve). The Militia resurfaced briefly as an Army Reserve between 1954 and 1968.

The related problem is: "who has the authority to call out the "Militia"" regardless of what it is called. The historical, traditional, answer is that the Crown's agent, specifically its Lieutenant (either Lord-Lieutenant or Lieutenant-Governor) or its Attorney (the Attorney General) and the Attorney's deputy, his Solicitor (the Solicitor General) have the authority to raise the Militia in defence of the Peace, Order and Good Governance within the realm.

On January 1 1867 Canada was not a realm. A collection of realms, each with their own Crown Lieutenant, Attorney and Solicitor, and their own Executive Council capable of making laws and advising their Crown Lieutenant, all permitted to arm and equip their citizenry to defend themselves and keep order, were debating how much sovereignty to cede to John A MacDonald and his proposed government.

John A. was determined to have a powerful central government. The Provinces demurred.

Regardless John A. managed to establish his authority under his own Crown Lieutenant. His Crown Lieutenant, his Lieutenant-Governor, however, was to be titled Governor-General. His intent was that this would the First Among Equals and be the senior Crown Lieutenant in Canada. That was the official position until 1882

en.wikipedia.org

That ruling stands.

Despite the wishes of the Federal Government and Wikipedia, the Provinces, their Lieutenants Governor, their Attorneys and Solicitors General, and their Executive Councils and Legislators, and their Militias, are not subordinate to Federal Authority. They are Co-Equal. And that includes maintaining the ability to call out the Miliitia, even when that Militia is centralized as a common good, renamed as the Canadian Forces, and jointly commanded by the Chief of the Defence Staff who finds him/her self in the invidious position of having to serve 11 masters.

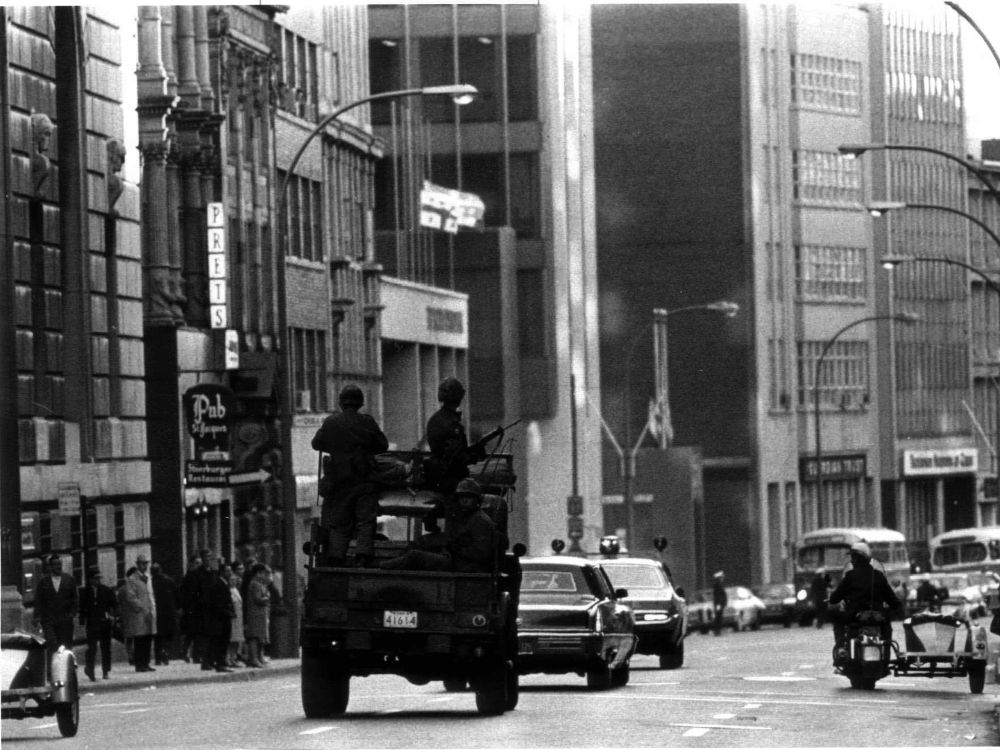

It would be an interesting day at the office if the Quebec Attorney General called out the Army to support the Surete de Quebec at the same time as the Attorney General of Canada called out the Army to support the RCMP over a dispute in the Province of Quebec.

No doubt the 2004 ruling, concurrent with the debates over Quebec sovereignty, was influenced by considerations of that thought. But what appears to by a minor administrative change is actually a major rebalancing of the Crown authority within Canada.

The definition of sovereignty is the arrogation of lethal force in support of the government. Prior to 2004 and this modification it was clear that the Provinces had sovereign authority, even if they were temperate in how they interpreted that. After the modification they had been stripped of that sovereign authority and now had to justify their claim to the Federal government.

The could no longer "requisition". They could only "request". The CDS was no longer their employee. He served strictly as an employee of the Federal government.

Note -

One problem I have with the study of history in Canada, especially as perceived by modern community, is the failure to teach context. Especially historical context. Laws do not arise out of nothingness. They are created in a specific time and place to address a specific problem.

Three examples that engage me are slavery, religion and the militia. I regularly hear the discussion about both and their isolated impacts in the modern world of Canada, or the US, or the UK or France etc. But all of them are mixed over time and space and do not respect borders.

There were slavers and abolitionists of all religions and under all governments in all places. There were French and Irish protestants as much as there were English Roman Catholics. And the Militia Act of 1855 was not a purely Canadian Bill, it was part of an Empire wide response to concerns about Louis Napoleon and his desire to re-establish French Empire - a desire that manifested itself in the French-Mexican wars and support of the Vatican against the "liberal" forces of Garibaldi and Victor Emmanuel of Savoy.

Context matters.

nationalpost.com