You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Chinese Military,Political and Social Superthread

- Thread starter nULL

- Start date

OldSolduer

Army.ca Relic

- Reaction score

- 16,353

- Points

- 1,260

To clarify, Cantonese are a Han sub-group.

China has 56 ethnic groups - Han with about 92% of the population in the PRC, and 55 minorities.

Ok kind of a serious question - what percentage of Chinese people have some Mongolian DNA?

The Mongols are such an interesting subject.

- Reaction score

- 20,289

- Points

- 1,280

Probably a fair amount in the north. The Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) was officially when China was ruled by Kublai Khan and his successors.Ok kind of a serious question - what percentage of Chinese people have some Mongolian DNA?

The Mongols are such an interesting subject.

Mongolians are also an ethnic group in China - there are more Mongolians in Inner Mongolia (a region within China) than in the country of Mongolia itself.

Spencer100

Army.ca Veteran

- Reaction score

- 2,202

- Points

- 1,040

Patches! I know this group loves morale patches

Kind of sucks the that Winnie the Pooh is getting punched. With his Canadian connection.......but then on the other hand......Justin?

Kind of sucks the that Winnie the Pooh is getting punched. With his Canadian connection.......but then on the other hand......Justin?

RangerRay

Army.ca Veteran

- Reaction score

- 4,211

- Points

- 1,260

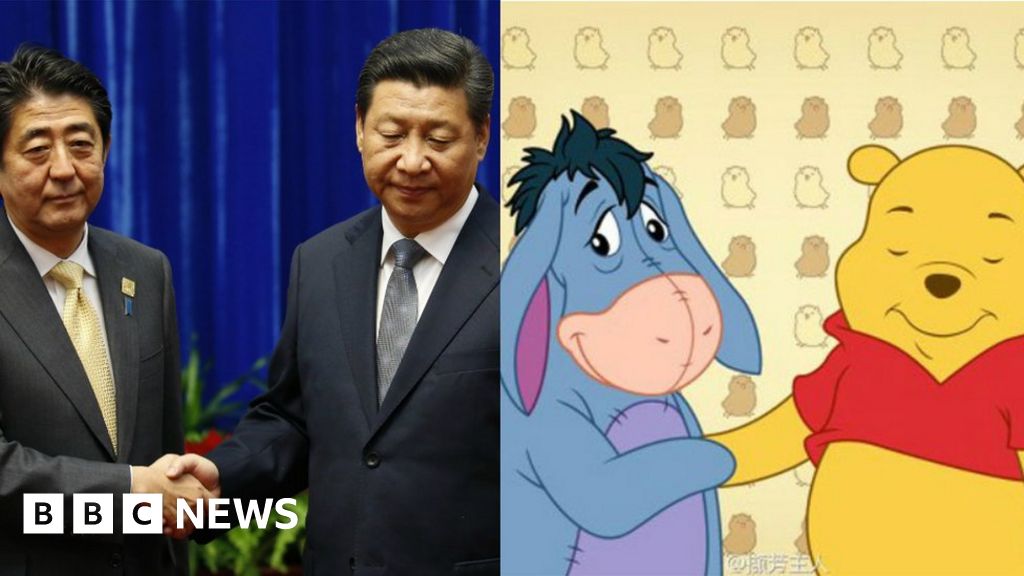

Apparently people in China were making memes online comparing Xi to Winnie the Pooh, so Pooh Bear was banned in China.

So Pooh = Xi

www.bbc.com

www.bbc.com

So Pooh = Xi

Why China censors banned Winnie the Pooh

The Bear of Very Little Brain joins a long line of funny internet references to China's top leaders.

daftandbarmy

Army.ca Dinosaur

- Reaction score

- 34,116

- Points

- 1,160

Apparently people in China were making memes online comparing Xi to Winnie the Pooh, so Pooh Bear was banned in China.

So Pooh = Xi

Why China censors banned Winnie the Pooh

The Bear of Very Little Brain joins a long line of funny internet references to China's top leaders.www.bbc.com

Uh oh, you know what this means, right?

Some fallout beginning to occur.

www.nationalnewswatch.com

www.nationalnewswatch.com

CEO, board of Trudeau Foundation resign citing recent politicization of their work | National Newswatch

National Newswatch: Canada's most comprehensive site for political news and views. Make it a daily habit.

OldSolduer

Army.ca Relic

- Reaction score

- 16,353

- Points

- 1,260

Maybe this is the start of the downfall of this government - which is more a cult of personality than a government.Some fallout beginning to occur.

CEO, board of Trudeau Foundation resign citing recent politicization of their work | National Newswatch

National Newswatch: Canada's most comprehensive site for political news and views. Make it a daily habit.www.nationalnewswatch.com

The phrase “Old Boys Club” seems particularly apt here.Maybe this is the start of the downfall of this government - which is more a cult of personality than a government.

GR66

Army.ca Veteran

- Reaction score

- 4,314

- Points

- 1,160

This article from the US Naval Institute website basically suggests a naval blockade might be the most effective strategy for the US in a conflict with China. Exploits China's supply vulnerability while minimizing the impact of their area denial systems.Exploiting China’s Maritime VulnerabilityBy Captain Michael Hanson, U.S. Marine CorpsApril 2023

While the concept is nothing new, the highlighted portions do suggest a possible role that Canadian forces could play in such a conflict. Rather than investing in a "big honking ship" or a nuclear submarine fleet (and all the expenses related) we could focus on expanding our capability to board and capture enemy merchant ships from our CSCs.Proceedings

Vol. 149/4/1,442

China’s antiaccess/area-denial (A2/AD) strategy is designed to give it the space it needs to operate unmolested in its near abroad. Its arsenal of missiles threatens any ship that enters its weapons engagement zone. As a counter, the Marine Corps has developed the concept of stand-in forces—strategically placed, light, highly mobile units that can “persist independently for days if needed and can reposition with organic mobility assets to avoid being targeted.”1

In short, these distributed and decentralized forces seek to turn the A2/AD against China, keeping its fleet in its home ports.

However, there is another option. China has the second largest economy in the world and, as such, has an enormous appetite for raw materials. In a single year, it imports upward of $150 billion of crude petroleum, $99 billion of iron ore, $36.6 billion in gasoline, and $31.7 billion of refined copper.2 Much of this arrives by sea.

Several different types of ships transport this cargo, and interdicting even one could disrupt Chinese commerce. For example, a single tanker can carry from 500,000 barrels of oil (Panamax tankers) up to 4,000,000 barrels (the Ultra Large Crude Carrier).3 Container ships that transport goods measure their capacity in 20-foot equivalent units (TEUs), after the standard 20 by 8 by 8 foot containers. Panamax ships can load 3,000–3,400 TEUs. The Very Large and Ultra Large Container Ships can transport more than 24,000 TEUs.4

China’s dependence on extended overseas supply lines makes it politically and economically vulnerable. This is a critical vulnerability that, in the event of conflict, could be targeted. And U.S. Marines could help.

Whether the ships transporting China’s vital cargo are tankers or container ships, the majority will transit the South China Sea.5 This trade route could easily be cut off by interdicting the shipping lanes at a few key maritime choke points in the Indian Ocean, specifically, the Lombok and Sunda Straits in Indonesia and the Strait of Malacca between Indonesia and Malaysia. The United States also could choke off Chinese shipping at the other ends of these supply lines at the Strait of Hormuz, where the Persian Gulf meets the Indian Ocean, and the Bab el-Mandeb, where the Red Sea joins the Gulf of Aden.

The U.S. Navy could sit outside China’s weapons engagement zone and interdict ships as they approach these key choke points. U.S. submarines could do to China’s merchant fleet what they did to Japan’s during World War II. But such a campaign would not need be carried out solely by the Silent Service. Navy surface ships could disrupt China’s cargo fleet, as could Marines.

Marine expeditionary units could reinvent themselves as attack groups, launching Marines by rotary-wing aircraft or small boat to board and seize Chinese merchant ships on the high seas. Once the ships were secured, the Marines could scuttle them with their cargo, turn them over to a new crew to pilot to impoundment in a friendly port, or even bring their cargoes to market in support of the U.S. war effort. Should China’s navy come out from under its protective A2/AD bubble and face U.S. and allied fleets on the high seas, it would see significant losses. As such, China would face a dilemma.

The environmental impact of sinking oil tankers would argue for capturing and escorting these vessels to friendly ports. Marines would be ideally suited for boarding and seizing these ships. Such a strategy also would increase integration between the Navy and Marine Corps.

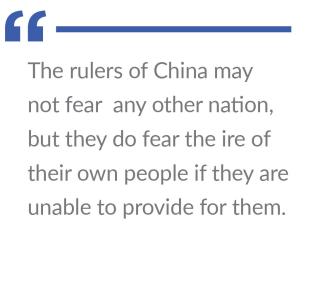

The Marine Corps can serve a vital role by exploiting a critical Chinese vulnerability to “create a turbulent and rapidly deteriorating situation with which the [adversary] cannot cope.”6 As China’s supply of vital resources dried up, and with the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps team preventing the import of sufficient resources to fuel its massive economic engine, the Chinese people would become restive. The rulers of China may not fear any other nation, but they do fear the ire of their own people if they are unable to provide for them. Unleashing a war on China’s maritime commerce is a daunting prospect that would not be undertaken lightly. But if necessary, it could affect China’s decision-making calculus and compel it to keep its fleet in its home ports and its soldiers in their barracks.

- Reaction score

- 6,166

- Points

- 1,260

Very interesting article in Foreign Affairs by Alexander Gabuev (Director of the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center):

"A decade ago, the Kremlin was reluctant to sell cutting-edge military technology to China. Moscow worried that the Chinese might reverse engineer the technology and figure out how to produce it themselves. Russia also had broader concerns about arming a powerful country that borders the sparsely populated and resource-rich Russian regions of Siberia and the Far East. But the deepening schism between Russia and the West following the 2014 annexation of Crimea changed that calculus. And after launching a full-scale war in Ukraine and prompting the complete breakdown of ties with the West, Moscow has little choice but to sell China its most advanced and precious technologies ... [and] ... Even before the war, some Russian analysts of China’s defense industry had advocated entering into joint projects, sharing technology, and carving out a place in the Chinese military’s supply chain. Doing so, they argued, offered the best way for the Russian military industry to modernize—and without that progress, the rapid pace of China’s own R & D would soon render Russian technology obsolete. Today, such views have become conventional wisdom in Moscow. Russia has also started opening up its universities and science institutes to Chinese partners and integrating its research facilities with Chinese counterparts. Huawei, for example, has tripled its research staff in Russia in the wake of a Washington-led campaign to limit the Chinese tech giant’s global reach."

"Neither Beijing nor Moscow has any interest in disclosing the details of any of the private discussions held during the Xi-Putin summit. The same goes for details on how Russian companies could gain better access to the Chinese financial system—which was the reason why Elvira Nabiullina, chair of Russia’s central bank, was a significant participant at the bilateral talks. That access has become critical for the Kremlin, since Russia is rapidly becoming more dependent on China as its main export destination and as a major source of technological imports, and as the yuan is becoming Russia’s preferred currency for trade settlement, savings, and investments .. [and] ... The participation of the heads of some of the biggest Russian commodity producers indicates that Xi and Putin also discussed expanding the sale of Russian natural resources to China. Right now, however, Beijing has no interest in drawing attention to such deals, in order to avoid criticism for providing cash for Putin’s war chest. In any case, Beijing can afford to bide its time, since China’s leverage in these quiet discussions is only growing: Beijing has many potential sellers, including its traditional partners in the Middle East and elsewhere, whereas Russia has few potential buyers." China would rather buy natural resources - at fire-sale prices - than "take" them by coercion, but it has an existential need for those resources.

"The Chinese-Russian relationship has become highly asymmetrical, but it is not one-sided. Beijing still needs Moscow, and the Kremlin can provide certain unique assets in this era of strategic competition between China and the United States. Purchases of the most advanced Russian weapons and military technology, freer access to Russian scientific talent, and the rich endowment of Russia’s natural resources—which can be supplied across a secure land border—make Russia an indispensable partner for China. Russia also remains an anti-American great power with a permanent seat on the UN Security council—a convenient friend to have in a world where the United States enjoys closer ties with dozens of countries in Europe and the Indo-Pacific and where China has few—if any—real friends. China’s connections are more overtly transactional than the deeper alliances Washington maintains ... [and] ... That means that although China wields great influence in the Kremlin, it does not exert control. A somewhat similar relationship exists between China and North Korea. Despite the enormous extent of Pyongyang’s dependency on Beijing, and shared animosity toward the United States, China cannot fully control Kim Jong Un’s regime and needs to tread carefully to keep North Korea close. Russia is familiar with this kind of relationship since it maintains a parallel one with Belarus, in which Moscow is the senior partner that can pressure, cajole, and coerce Minsk—but cannot dictate Belarusian policy across the board."

Alexander Gabuev concludes that: "Russia’s size and power may give the Kremlin a false sense of security as it locks itself into an asymmetrical relationship with Beijing. But the durability of this relationship, absent major unforeseeable disruptions, will depend on China’s ability to manage a weakening Russia. In the years to come, Putin’s regime will have to learn the skill that junior partners the world over depend on for survival: how to manage upward."

"A decade ago, the Kremlin was reluctant to sell cutting-edge military technology to China. Moscow worried that the Chinese might reverse engineer the technology and figure out how to produce it themselves. Russia also had broader concerns about arming a powerful country that borders the sparsely populated and resource-rich Russian regions of Siberia and the Far East. But the deepening schism between Russia and the West following the 2014 annexation of Crimea changed that calculus. And after launching a full-scale war in Ukraine and prompting the complete breakdown of ties with the West, Moscow has little choice but to sell China its most advanced and precious technologies ... [and] ... Even before the war, some Russian analysts of China’s defense industry had advocated entering into joint projects, sharing technology, and carving out a place in the Chinese military’s supply chain. Doing so, they argued, offered the best way for the Russian military industry to modernize—and without that progress, the rapid pace of China’s own R & D would soon render Russian technology obsolete. Today, such views have become conventional wisdom in Moscow. Russia has also started opening up its universities and science institutes to Chinese partners and integrating its research facilities with Chinese counterparts. Huawei, for example, has tripled its research staff in Russia in the wake of a Washington-led campaign to limit the Chinese tech giant’s global reach."

"Neither Beijing nor Moscow has any interest in disclosing the details of any of the private discussions held during the Xi-Putin summit. The same goes for details on how Russian companies could gain better access to the Chinese financial system—which was the reason why Elvira Nabiullina, chair of Russia’s central bank, was a significant participant at the bilateral talks. That access has become critical for the Kremlin, since Russia is rapidly becoming more dependent on China as its main export destination and as a major source of technological imports, and as the yuan is becoming Russia’s preferred currency for trade settlement, savings, and investments .. [and] ... The participation of the heads of some of the biggest Russian commodity producers indicates that Xi and Putin also discussed expanding the sale of Russian natural resources to China. Right now, however, Beijing has no interest in drawing attention to such deals, in order to avoid criticism for providing cash for Putin’s war chest. In any case, Beijing can afford to bide its time, since China’s leverage in these quiet discussions is only growing: Beijing has many potential sellers, including its traditional partners in the Middle East and elsewhere, whereas Russia has few potential buyers." China would rather buy natural resources - at fire-sale prices - than "take" them by coercion, but it has an existential need for those resources.

"The Chinese-Russian relationship has become highly asymmetrical, but it is not one-sided. Beijing still needs Moscow, and the Kremlin can provide certain unique assets in this era of strategic competition between China and the United States. Purchases of the most advanced Russian weapons and military technology, freer access to Russian scientific talent, and the rich endowment of Russia’s natural resources—which can be supplied across a secure land border—make Russia an indispensable partner for China. Russia also remains an anti-American great power with a permanent seat on the UN Security council—a convenient friend to have in a world where the United States enjoys closer ties with dozens of countries in Europe and the Indo-Pacific and where China has few—if any—real friends. China’s connections are more overtly transactional than the deeper alliances Washington maintains ... [and] ... That means that although China wields great influence in the Kremlin, it does not exert control. A somewhat similar relationship exists between China and North Korea. Despite the enormous extent of Pyongyang’s dependency on Beijing, and shared animosity toward the United States, China cannot fully control Kim Jong Un’s regime and needs to tread carefully to keep North Korea close. Russia is familiar with this kind of relationship since it maintains a parallel one with Belarus, in which Moscow is the senior partner that can pressure, cajole, and coerce Minsk—but cannot dictate Belarusian policy across the board."

Alexander Gabuev concludes that: "Russia’s size and power may give the Kremlin a false sense of security as it locks itself into an asymmetrical relationship with Beijing. But the durability of this relationship, absent major unforeseeable disruptions, will depend on China’s ability to manage a weakening Russia. In the years to come, Putin’s regime will have to learn the skill that junior partners the world over depend on for survival: how to manage upward."

GR66

Army.ca Veteran

- Reaction score

- 4,314

- Points

- 1,160

The highlighted portion is closely related to the article I posted above about the strategy of a naval blockade of China in case of a conflict. China knows very well that its maritime trade routes are highly vulnerable and I'm sure is desperate to find secure alternate overland routes for as much of its key resources as possible.Very interesting article in Foreign Affairs by Alexander Gabuev (Director of the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center):

"The Chinese-Russian relationship has become highly asymmetrical, but it is not one-sided. Beijing still needs Moscow, and the Kremlin can provide certain unique assets in this era of strategic competition between China and the United States. Purchases of the most advanced Russian weapons and military technology, freer access to Russian scientific talent, and the rich endowment of Russia’s natural resources—which can be supplied across a secure land border—make Russia an indispensable partner for China. Russia also remains an anti-American great power with a permanent seat on the UN Security council—a convenient friend to have in a world where the United States enjoys closer ties with dozens of countries in Europe and the Indo-Pacific and where China has few—if any—real friends. China’s connections are more overtly transactional than the deeper alliances Washington maintains ... [and] ... That means that although China wields great influence in the Kremlin, it does not exert control. A somewhat similar relationship exists between China and North Korea. Despite the enormous extent of Pyongyang’s dependency on Beijing, and shared animosity toward the United States, China cannot fully control Kim Jong Un’s regime and needs to tread carefully to keep North Korea close. Russia is familiar with this kind of relationship since it maintains a parallel one with Belarus, in which Moscow is the senior partner that can pressure, cajole, and coerce Minsk—but cannot dictate Belarusian policy across the board."

Overland trade routes from Russia would pretty be secure from Western attempts to disrupt the movement of goods as any attacks on Russian territory would likely draw Russia directly into the conflict. Routes through other, non-nuclear "minor" powers (the "Stans", Myanmar, Laos, etc.) on the other hand could potentially face disruption by Western military forces if deemed necessary. The problem for China though is the huge volume of material that can be transported by sea compared to overland.

- Reaction score

- 6,166

- Points

- 1,260

Repeating myself, I know, but I was told, back in the late 1990s, by a Chinese official that resources, especially water, were China';s main weakness. Siberia, he explained, was a treasure-trove of resources and has three major wantersheds. At the time I understood that China's strategic aim was to 'separate' Siberia from Russia: there former were to become two or three 'independent' republics - Chinese casual states; the latter was to become a European power, aligned with China.

Others have told me that China is happy enough to leave Siberia in Russian hands so long as Russia is, as Gabuev suggests, a compliant junior partner - rather like Canada to the USA.

-----

Edited to add: readers must remember that I was on duty in China, negotiating with them and other Asian nations, about matters related to the global use of the radio spectrum. I was a guest of the Chinese government and I took full advantage to learn as much as I could. My hosts knew that everything they said to me would be reported back to my government and I know that everything I said would be taken down and analyzed. I found (1990s and early 2000s) that the Chinese in my business - Ministries of Commerce and Defence - were quite open and even eager to show me China, even a few of the warts; they were proud pf their country and of what it was becoming: a great power. While they admired Canada for its natural advantages they left no doubt that they regarded Canada as a US colony.

Others have told me that China is happy enough to leave Siberia in Russian hands so long as Russia is, as Gabuev suggests, a compliant junior partner - rather like Canada to the USA.

-----

Edited to add: readers must remember that I was on duty in China, negotiating with them and other Asian nations, about matters related to the global use of the radio spectrum. I was a guest of the Chinese government and I took full advantage to learn as much as I could. My hosts knew that everything they said to me would be reported back to my government and I know that everything I said would be taken down and analyzed. I found (1990s and early 2000s) that the Chinese in my business - Ministries of Commerce and Defence - were quite open and even eager to show me China, even a few of the warts; they were proud pf their country and of what it was becoming: a great power. While they admired Canada for its natural advantages they left no doubt that they regarded Canada as a US colony.

RangerRay

Army.ca Veteran

- Reaction score

- 4,211

- Points

- 1,260

From Andrew Coyne. Watergate was blown open by “unnamed sources”. Attacks on reporting using unnamed or anonymous (not to the reporter) sources are deflections.

www.theglobeandmail.com

www.theglobeandmail.com

Opinion: ‘These stories are based on unnamed sources,’ and other Liberal deflections

It is plainly in the public interest to know by what means China attempted to tilt our elections, and with what assistance from domestic sources

So their position can’t possibly be that this sort of thing just shouldn’t be reported – even if true. Is it, then, that a reporter who is given evidence of this should refuse to report it unless their sources publicly identify themselves? But that, in the circumstances, amounts to saying it should not be reported: It is not just career-ending but illegal for intelligence officials to leak classified information. Unnamed sources are a critical part of investigative reporting, and were long before Watergate.

- Reaction score

- 23,229

- Points

- 1,360

Similarities in the process of reporting notwithstanding, the difference between Watergate and (at the risk of being labeled as a *‘racist’ by Trudeau-supporters, using the term) Chinagate, is that Watergate was a home-grown partisan issue, not another external state’s deliberate actions to influence political/electoral outcomes of a (for now) sovereign nation.From Andrew Coyne. Watergate was blown open by “unnamed sources”. Attacks on reporting using unnamed or anonymous (not to the reporter) sources are deflections.

Opinion: ‘These stories are based on unnamed sources,’ and other Liberal deflections

It is plainly in the public interest to know by what means China attempted to tilt our elections, and with what assistance from domestic sourceswww.theglobeandmail.com

Last edited:

- Reaction score

- 23,229

- Points

- 1,360

Tell us you think they have proof he knew and you told him, without telling us you think they have proof that he knew and you told him…

apple.news

apple.news

'Quite possible' Trudeau briefed on election interference in January 2022, Katie Telford says

China's Consul General threatens Tory MP Bob Saroya before 2021 election, committee hears — Global News

Katie Telford, Justin Trudeau's most trusted aide, told a parliamentary committee about intelligence briefings the prime minister received on foreign election interference.

- Reaction score

- 8,537

- Points

- 1,160

The highlighted portion is closely related to the article I posted above about the strategy of a naval blockade of China in case of a conflict. China knows very well that its maritime trade routes are highly vulnerable and I'm sure is desperate to find secure alternate overland routes for as much of its key resources as possible.

Overland trade routes from Russia would pretty be secure from Western attempts to disrupt the movement of goods as any attacks on Russian territory would likely draw Russia directly into the conflict. Routes through other, non-nuclear "minor" powers (the "Stans", Myanmar, Laos, etc.) on the other hand could potentially face disruption by Western military forces if deemed necessary. The problem for China though is the huge volume of material that can be transported by sea compared to overland.

Historically 'land routes" have been the most problematic. All it takes is a group of locals and a pile of pallets at a strategic location and the next thing you know you are paying tribute.

- Reaction score

- 8,537

- Points

- 1,160

Similarities in the process of reporting notwithstanding, the difference between Watergate and (at the risk of being labeled as a ‘facist’ by Trudeau-supporters, using the term) Chinagate, is that Watergate was a home-grown partisan issue, not another external state’s deliberate actions to influence political/electoral outcomes of a (for now) sovereign nation.

I found it bizarre that Coyne considered the domestic Watergate case to be more problematic than the foreign "Chinagate" case.

RangerRay

Army.ca Veteran

- Reaction score

- 4,211

- Points

- 1,260

I think he was showing that attempts were made to discredit Woodward and Bernstein for using unnamed sources in Watergate just as the Liberals are trying discredit Fife, Chase and Cooper for also using unnamed sources. It doesn’t matter if they’re unnamed if what they say is true.I found it bizarre that Coyne considered the domestic Watergate case to be more problematic than the foreign "Chinagate" case.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 9K

- Replies

- 26

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 2

- Views

- 6K