Canada works best when there’s vigorous political competition. That’s why the conversation Canadian conservatives have been having of late, at the Manning Centre Conference in Ottawa, in Alberta and among Ontario Progressive Conservatives at their convention on the weekend, is important.

A glance at conservatives south of the border should make everyone here recognize how poorly voters are served when political parties fall to fractiousness and infighting.

Parties are messy, imperfect organisms – they often make the choices that reinforce, not reverse, their weaknesses. As Canadian conservatives think about the road ahead, some research we’ve done into the Canadian psyche is worth a look.

In Canada’s last election, lots of voters were fed up with the prime minister. There wasn’t much happiness with the incumbents, but there were also doubts about the challengers.

In truth, there wasn’t enough anger or fear to elect anyone.

For the New Democrats, it probably felt like second nature to seek out and stoke anger on the campaign trail. Surrounded by partisans of the left and the far left, theirs was a group chat among people furious about 10 years of public policy that insulted their values.

What’s more, the NDP was led by a man whose eyes lit up at every opportunity to express his revulsion with Stephen Harper’s Conservatives.

Whether authentic emotion, or skilled presentation, or competitive fire, it didn’t matter much in the end. One eternal truth about public anger is that it can’t be manufactured – it exists or it doesn’t. Even the most intense, fiery orators can’t make those who wake up in the morning feeling okay about their lives go to sleep convinced that they are in much worse shape than they thought.

Our recent data (from Abacus polls) on the mindset of Canadians revealed some fundamental realities about our collective psyche. While this data form a snapshot in time, and these patterns may fluctuate over time, they won’t shift fundamentally.

More than 80 per cent of us describe ourselves as happy, optimistic and hopeful. Only 23 per cent of us say we’re angry.

One of the secrets of the success of the Liberal strategy was the choice to campaign on optimism rather than anger.

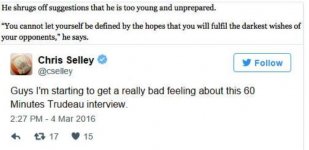

Perhaps this had more to do with the natural outlook of Justin Trudeau rather than a cold-eyed backroom calculation. Either way, looking back on the election results, while there are always many variables at play, one that stands out for me is that both the Conservatives and New Democrats mined for anger, when there wasn’t enough to go around.

Most days, Mr. Trudeau and the Liberals had the field of optimism, hope and happiness almost to themselves.

When you read the commentary of many conservatives today, there’s a common theme – a disbelief that people are happy, a conviction that they should be angry, a sense that “sunny ways” is a concoction of the Liberals and the hated mainstream media.

But any new Conservative leader should take a cold-eyed look at how Canadians describe themselves.

Eighty per cent are happy – 23 per cent are angry.

Eighty-three per cent are hopeful – 42 per cent are cynical.

Ninety per cent are open-minded – 58 per cent are set in their views.

Seventy per cent are progressive. Forty-four per cent are conservative.

Much of this isn’t really about specific public-policy preferences.

Many voters are interested in a wide range of conservative-oriented policies. Less red tape, lower taxes, safety from crime, open markets, entrepreneurship – it’s not hard to get people to back candidates who campaign on these ideas.

But too often in the past decade, conservative ideas have been served up with the hair-on-fire, attack-dog mentality typified by Ezra Levant.

The idea that to sell a good idea you must create an enemy and vilify them is far from the cleverest idea the conservatives ever had. It’s one of the worst. It’s their kryptonite.

When conservative partisans mock optimism, they are making fun of eight in 10 voters. It’s bad math.

When some conservatives reject new ideas about the environment and the economy, the 90 per cent of Canadians who are open-minded wish the Conservative Party was a little more open-minded regarding this agenda. Ontario’s PC Leader Patrick Brown seemed to embrace this idea on the weekend, offering his support for a revenue-neutral carbon-pricing plan.

In the jargon of U.S. primary politics, there’s a lot of talk about a “path to victory.”

In Canada, anyway, cynical and angry is not much of a path. Occasionally, those who travel it will get lucky. But conservative ideas have a far better chance of success if presented as the product of open minds, and optimistic thinking about the future of each and every one of us.