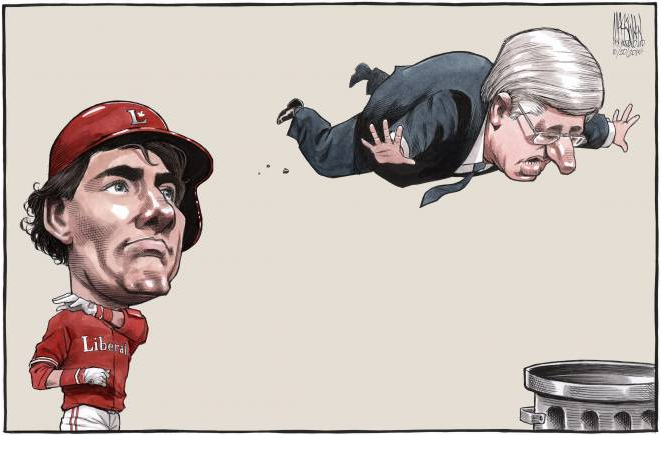

Defeat by Trudeau is the ultimate insult for Harper

SUBSCRIBERS ONLY

Jeffrey Simpson

OTTAWA — The Globe and Mail

Last updated Tuesday, Oct. 20, 2015

Losing power is bad enough; losing it to a Trudeau with a thumping majority is the ultimate political insult for Stephen Harper, who resigned on Monday night.

Everything in Mr. Harper’s political career from his early days as an assistant in Ottawa was directed at undoing or diluting as much as possible of prime minister Pierre Trudeau’s vision of government and Canada. Now, to be crushed by Mr. Trudeau’s son Justin, someone Mr. Harper considers intellectually weak and, worse, a chip off the old man’s block, must cut the Conservative Leader to the core.

Quebec-centred politics. Constitutional reform fixation. Large fiscal deficits. Expanding government. Regional development programs. Generous social programs. A meddling state. Middle-power internationalism without any definition of Canada’s interests. Tweaking the Americans’ nose. Mr. Harper interpreted as a mistake almost all of what he considered to be Pierre Trudeau’s legacy – a legacy his son has updated and placed in the 2015 Liberal Party’s platform.

This Liberal victory was stunning in that it was unforeseen until very, very recently. Stunning, too, was the Conservative defeat. The party’s low share of the popular vote ranked as one of the worst showings by a right-of-centre federal party in this century.

Mr. Harper will therefore be remembered for having won two minority governments and one majority and having been prime minister for nine years – an impressive accomplishment by any measure – but also for Monday’s defeat. And that defeat, more than any other explanation, reflected a widespread and deep aversion to his style of leadership, his persona and all the nicks and cuts that accumulate after nine years in office.

Time for a change is the oldest and most powerful force in a democracy. The Conservatives, as happens to a party long in power, ran on more of the same, whereas the country wanted something different.

The Liberals captured the desire for change much better than the New Democratic Party, which made tactical and strategic decisions that blew up in its face. The NDP read its own press clippings and believed Canadians considered the party prepared to govern, whereas it was, and remains, the third party in the country, notwithstanding the fluky 2011 result. The disappointment of Monday night will provoke much internal debate about leadership, long-term policy orientations and how to respond in the short term.

The two deepest emotions in politics are fear and hope. The Conservatives campaigned, especially towards the end, on fear of Mr. Trudeau, his inexperience and his policies. But after almost a decade of polarizing, bruising, partisan politics as practised by the Harper Conservatives, large swaths of the country wanted a different tone.

A lot of Canadians were tired of the politics of fear, preferring a message of hope. Mr. Trudeau gave it to them, albeit on a cloud of clichés and some improbable policies, arguing that change could come “now,” that he could bring people together rather than trying to divide them for political purposes, and that his youth, far from being a crippling liability, suggested energy and freshness after the sour and humourless politics that had gripped Ottawa.

Mr. Trudeau’s opponents underestimated and denigrated him (“He’s just not ready”). The attacks worked for a while, but then, as he refused to make mistakes, performed acceptably in televised debates, presented a platform that conformed with focus groups’ desire for activist government, Canadians gave the Liberal Leader a second look. He could, after all, walk and chew gum at the same time. Maybe he was “ready.” Maybe, a growing number of Canadians said to themselves, that time for a change meant him.

The Liberal decline from the election of 2004 had suggested that perhaps Canada was witnessing the strange death of Liberal Canada, but last night put paid to that idea. In many Western democracies, politics has evolved in ideological fights between right and left, with little room for centrist parties.

Monday’s result suggests that the old joke about Canadians crossing the road to get to the middle is not far off the mark.

Critics are already sniffing that the Liberals will once again campaign from the left but govern from the right. They have done it before. With rude shocks of reality awaiting the new government, do not be surprised if that Liberal pattern re-emerges.