John Ibbitson,

writing in the Globe and Mail, gives us a history lesson:

----------

What past party revolts can teach us about the internal Liberal rebellion targeting Justin Trudeau

JOHN IBBITSON

PUBLISHED YESTERDAY

On Sunday Feb. 3, 1963, cabinet ministers filed into the dining room at the prime minister’s residence – some angry, some confused, all worried that internal divisions had placed their Progressive Conservative government at risk. Then John Diefenbaker walked in.

The prime minister told his cabinet he wanted to dissolve Parliament and fight an election on American interference in Canadian affairs. Defence minister Douglas Harkness objected. You have lost our confidence, he declared. You should resign.

Mr. Diefenbaker leapt to his feet. Who is loyal? he demanded to know. Some rose, some stayed seated. The prime minister stalked out of the room, trailed by ministers who shouted “Traitor!” at those left behind.

Six decades later,

Justin Trudeau also faces an internal rebellion, led by a cabal of Liberal MPs who want the unpopular prime minister to resign.

All those involved should take care. History tells us that such revolts can make a party unelectable for many years.

Caucus

rebellions usually occur “when a leader so obviously demonstrates weakness and unpopularity,” Norman Hillmer, professor of history at Carleton University, said in an interview.

One of the worst was the cabinet split that brought down Mr. Diefenbaker.

Although his government had chalked up major successes – important reforms in immigration, health care and the justice system; a new bill of rights; leadership in the fight against apartheid – Mr. Diefenbaker’s increasingly erratic behaviour had made the Progressive Conservative prime minister unpopular with the public and many in his own party.

By the winter of 1963, his minority government was being torn apart over whether to accept nuclear-tipped Bomarc surface-to-air missiles from the United States as part of its commitment to North American air defence. Mr. Harkness wanted Canada to say yes to nuclear Bomarcs; external affairs minister Howard Green wanted Canada to say no. Mr. Diefenbaker couldn’t, or wouldn’t, decide.

After that stormy February meeting, Mr. Harkness and two other cabinet ministers resigned. Those resignations helped doom Mr. Diefenbaker in the 1963 election that made Lester Pearson Liberal prime minister.

Factional infighting helped keep the Tories out of power, with one brief exception, for more than two decades. That exception arrived in May, 1979, when Joe Clark led the PCs to a minority-government win against Pierre Trudeau’s Liberals.

But Mr. Clark’s government lost a vote of confidence over its first budget, resulting in an election in February, 1980, that delivered a fresh, majority-government mandate for Mr. Trudeau.

Over the next three years, Mr. Clark spent as much time fighting a rebellion within his own party as he did fighting the Liberals. Mr. Clark ultimately lost the leadership to Montreal businessman Brian Mulroney, who led the PCs to a huge majority-government victory the following year.

But though he worked hard to keep the party united, Mr. Mulroney’s caucus consisted of Quebec nationalists, populist conservatives and Red Tories. It was bound to fracture.

By 1993, Lucien Bouchard had led an exodus of MPs from caucus, forming the Bloc Québécois, and many conservatives were backing Preston Manning’s new Reform Party. The Progressive Conservatives were reduced to two seats in the fall election that gave Jean Chrétien’s Liberals a majority government.

For the next decade, divisions within the conservative movement doomed it to opposition status. But the Liberals were themselves divided.

Following their third majority-government win in 2000, finance minister Paul Martin openly and successfully conspired to force Mr. Chrétien to resign. By 2003, Mr. Martin was prime minister.

But the

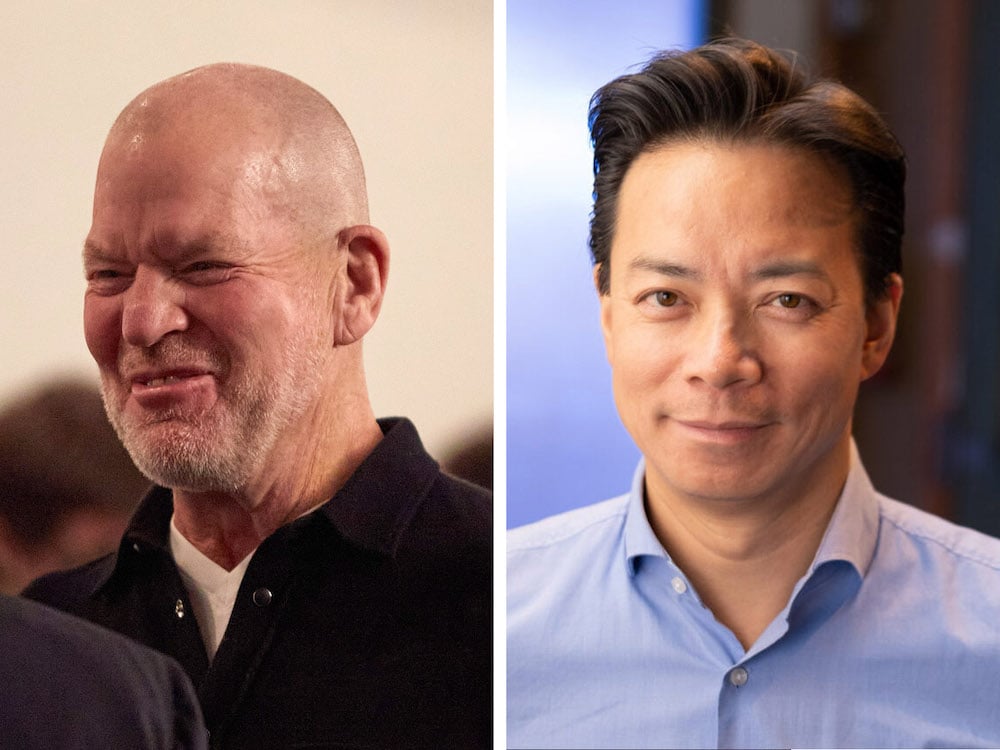

Liberals were tarnished by a scandal involving party kickbacks, while the right finally united as the new Conservative Party under Stephen Harper. By 2006, the Conservatives were in power. Bickering within the Liberal Party contributed to a decade in opposition, until Mr. Trudeau

unified the party and brought it power in 2015.

Now Mr. Trudeau faces his own caucus

revolt, with the Conservatives under Pierre Poilievre streets ahead in the polls. Caucus divisions risk dooming the Liberals once again to years in the wilderness.

But Robert Bothwell, professor emeritus of history at University of Toronto, offers this consolation: Internal party splits “are bad, but not necessarily fatal,” he told me.

Both the Tories and the Grits have stabbed themselves in the back more than once. But sooner or later, both rose again.

----------

Parenthetically, I remember the Diefenbaker/Harkness thing very well. I was a young, junior NCO, serving in a Honest John missile battery in Camp Shilo and we - and our missiles - were part of the crisis and we knew it.

But the bigger lesson is that parties are very human things and people can disagree on matters of principle and leaders can find it hard to decide on big questions of principle.