Britain’s accession to the world’s most dynamic trade pact is the end of the Rejoiner dream

The CPTPP deal is a direct challenge to Brussels' protectionist doctrines

AMBROSE EVANS-PRITCHARD31 March 2023 • 6:00am

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak quickly follows the Windsor Framework with the CPTPP deal CREDIT: Rory Arnold / No 10 Downing Street

Rishi Sunak is on a roll. The Windsor Framework begins to put Britain’s trade relations with Europe on a workable foundation, and without having to submit to European legal and political suzerainty.

Britain’s imminent

accession to the Pacific free trade pact helps him finish the job. The accord instantly raises Britain’s bargaining power in dealings with the EU, and sets in motion a process that shatters a host of Rejoiner shibboleths.

“It is not about immediate trade figures: it is about the geopolitical dynamic in world trade over the next 20 or 30 years. It raises the UK’s status enormously in the global economy,” said Professor David Collins, an expert on world trade at City University.

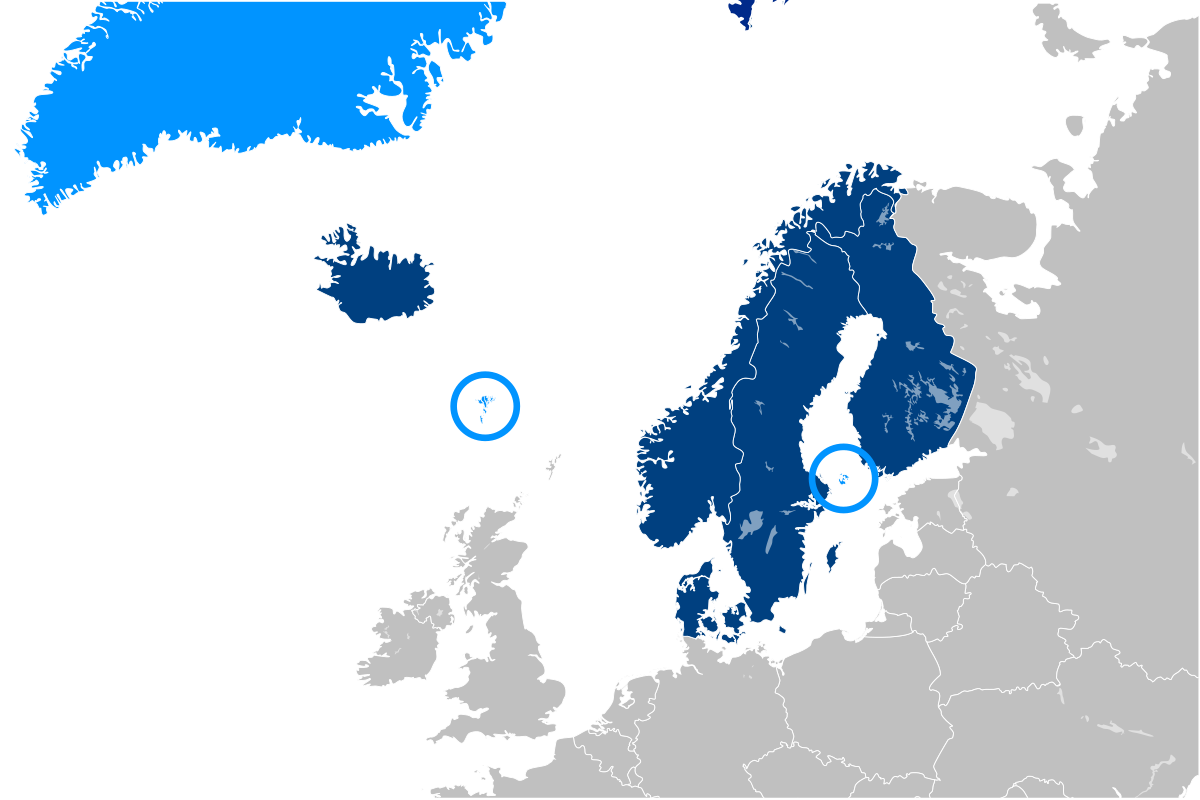

The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) comprises Japan, Canada, Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, Mexico, Peru, Chile, Australia, New Zealand, and Brunei. It jumps overnight to 16pc of global GDP once Britain joins, leap-frogging the combined EU.

The Pacific bloc is heading rapidly for 20pc as a string of states in the Far East and Latin America signal an intent to join, at which point it becomes a stampede. By the end of this decade it will probably be the world’s largest trading system by a wide margin, increasingly able to set the tone and rules of global commerce.

This revenge of the ‘middle powers’

demolishes the central catechism of Britain’s pro-EU trade elites: that the world is divided into three regulatory blocs – the US, EU, and China – and that the underlings must buckle under and accept the terms.

“This is a seismic event. The EU and the US fully understand the geo-economic significance of this, and are utterly shocked that it could have happened,” said Shanker Singham, a UK trade adviser and a fellow at the Institute of Economic Affairs.

“It is a wake-up call in Washington. It is now much more likely that we’ll see a US-UK bilateral trade deal, and there is going to be a chorus of calls for the US itself to join the CPTPP,” he said.

As a practical matter, UK accession kills off any likelihood that it will ever rejoin the EU customs union or single market. There will be no ‘dynamic alignment’ with EU directives. The course is set irreversibly in a different direction.

The CPTPP members have one shared objective: to make trade as smooth and easy as humanly possible, subject to basic civilised standards. It is governed by twin principles of mutual recognition and equivalence.

This is entirely at odds with EU ideology. Brussels obliges supplicants to adopt identical laws, rules, and standards – under the writ of the European Court – in order to secure access to the European market. It does not accept reciprocation as a governing principle of trade.

The EU’s neo-colonial ambitions have reached obvious limits. Its share of global GDP will drop to 14.6pc this year. It is losing roughly one percentage point every three years. Europe will remain a valuable market. Its regulatory apparatus will punch above its weight for a while yet.

Yet the EU is undergoing a slow, comfortable, economic relegation, trailing badly in the Sino-US technology arms race, and politically captured by corporate vested interests wedded to the status quo - a reflex on display over the last week as the

German car industry won a (futile) reprieve for 20th century combustion engines.

“The EU’s dream of being a global regulatory superpower was never what it was cracked up to be and from now on it is going into decline. I don’t think it is going to be exporting its rules or precautionary principle for much longer,” said Prof Collins.

The tide is already receding over digital data. Japan, Singapore, and Korea are embarking on their own soft-touch regimes rather than swallowing the EU’s rule-heavy GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) – a nightmare for small business.

The CPTPP has a “trade-driven” philosophy. Its chapter on small business is designed to promote easy access to information for start-ups and hi-tech firms, rather than seeking to restrict it. The pact reduces the burden of

rules of origin in cross-border commerce to the absolute minimum with self-certification and paperless trade, unlike the bureaucratic overkill of the EU’s customs regime - sheer torture for small British exporters trying to ship goods across the Channel.

The EU never delivered on free trade in services. National barriers proved intractable and Brussels failed to enforce its own laws. This was a chronic grievance for the UK as the world’s second largest exporter of services. “The CPTPP goes much further in opening up e-commerce and financial services,” said Prof Collins.

Britain’s pro-Brussels camp has always ridiculed UK’s Pacific tilt as grandstanding, an implausible attempt to put flesh on the bones of Global Britain. The Pacific is far away and the volumes are trivial. The canonical ‘gravity’ model of trade is solemnly invoked, even though it has less traction in the digital age. We are told that the CPTPP can never be a swap for lost EU trade.

But it is not intended to be a swap. It is better understood as a direct challenge to the EU’s protectionist trade doctrines. It is an attempt to assert a rival Peelite doctrine of open global trade. It is a bid to seize intellectual leadership as the paralysed World Trade Organisation enters its agonies. “There is a battle going on over the operating system for global trade. The EU is going to discover that it can’t impose its laws on other countries,” said Mr Singham.

British accession to the CPTPP matters in the international political dance. It brings added G7 heft and free-market credibility at a critical moment. Taiwan, Korea, Thailand, Uruguay, Colombia, Ecuador, and Costa Rica have either applied or talked of doing so. The Philippines and Indonesia are exploring the option. China has also applied to join, which concentrates the mind in Washington.

Xi Jinping’s China is clearly not fit for membership today. His Leninist state-capitalism breaches a requirement that private and state companies must operate on a level-playing field. Uyghur concentration camps violate the pact’s labour standards. Nevertheless, Beijing could muscle in at some point and gain a lockhold over the Pacific trading system if the US stands aloof.

The US was a key driver of the original Pacific accord (TTP) under Barack Obama. It was intended to counter China’s push for hegemony in Asia. Donald Trump

made it the scarecrow of his electoral campaign in 2016 and later pulled out theatrically, inflicting enormous damage on US strategic interests in the Far East. The Democrats have since been loath to touch it, believing that it cost Hillary Clinton the presidency.

There is by now broad agreement in US foreign policy circles that walking away was a gift to China, and an unforgivable squandering of US credibility in Asia. “The US needs to learn from its TPP mistake and get its seat back at the table,” say Senators Tom Carper and John Cornyn, leaders of a bipartisan coalition in favour of revisiting the issue.

Whatever happens, the UK is about to join a large, open, dynamic free trade grouping that is open to new technology and congenial for sovereign self-governing nations under their own laws. It can look forward to a bilateral deal with the US sooner than most had supposed.

The trading arrangements that free trade Brexiteers had always hoped to see are finally taking shape. Good work Prime Minister.

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/V42JAAMI5JOO5MHWMNLHC2J5CU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/QHSG7QSQMRICZCZFPQHNQBPT7I.jpg)