MarkOttawa said:April 13, from Stéphane Dion's close adviser Jocelyn Coulon--excerpts:

Quel Charlie Foxtrot, eh?

Mark

Ottawa

The article is a lengthy one. I had to translate it via Google Translate in four or five chunks. To save others from that inconvenience, I have consolidated said chunks and posted them here (and specifically not in the lengthy articles thread):

The day Trudeau disappointed the UN

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau broke a key promise by refusing to re-engage 600 soldiers in UN peacekeeping missions. International Relations Specialist and News Contributor Jocelyn Coulon, who was an advisor to Canada's Foreign Affairs Minister Stéphane Dion, is backstage on this flip-flop.

Angelina Jolie slowly advances to the platform where a hundred Defense Ministers gather for the traditional family photo. She is the distinguished guest of the United Nations Defense Ministers' Meeting on Peacekeeping held in Vancouver on November 15, 2017. The megastar is an eye-catcher. The actress is an icon, and Justin Trudeau loves icons, especially when he uses them to dazzle an audience and serve as a backdrop to mask the announcement of a policy without ambition.

The Vancouver meeting has a very specific goal: the states represented in the room must announce a real commitment to UN peace operations, not just an intention to contribute. And as Canada hosts the meeting, the audience is eagerly awaiting the Prime Minister's speech, an impatience all the more justified by the fact that Trudeau has made Canada's return to peace operations a key promise of his electoral platform. This policy is against the Conservative government, which, during its nine years in power, has shown the greatest disregard for peacekeeping and peacekeepers.

After a long and tortuous speech, in which form wins out on the bottom, the audience realizes that Canada is backing away. His contribution will be modest. What is going on ?

Peacekeeping is of particular interest to Minister Stéphane Dion. It is largely for this reason that he recruits me as a political adviser. Upon my arrival, he asks me to work on this file and write several speeches on the issue. The development of a new strategy for Canada's re-engagement in peace operations mobilizes the energies of several departments, particularly those of Foreign Affairs, National Defense and Public Safety, as well as the Prime Minister's Office. In Minister Dion's office, it is Christopher Berzins, the policy director, and I, who are working on this issue.

This policy has three elements: a guidance document entitled Canada's Strategy for Reengagement in United Nations Peace Operations, which frames and flags the peacekeeping policy for the coming years; the five-year renewal of the International Peacekeeping Police Program, which allows Canada to deploy up to 150 police officers in theaters of operations; and the creation of the Stabilization and Peace Operations Program with $ 150 million in annual funding over the next three years to support conflict prevention, mediation and dialogue initiatives. and reconciliation, improve the effectiveness of peace operations, support fragile states and respond quickly to crises.

National Defense is taking advantage of the press conference [August 26, 2016] to confirm its ability to deploy up to 600 Canadian Armed Forces personnel in UN peace operations. Everything is in place, except for one element: where exactly does the government want to deploy the Canadian military and police contribution? And that's where everything gets stuck.

The African continent hosts the six largest UN peace operations: Côte d'Ivoire, Darfur, Mali, Central African Republic, South Sudan and Democratic Republic of Congo. We are quickly eliminating the first two and focusing on the other four, because they are difficult missions where the United Nations needs strong material and political support from its member states, particularly the industrialized countries. They have heavy equipment and specialized quotas to perform certain tasks. The four peace operations we are targeting are the subject of in-depth analysis. Minister of National Defense Harjit Sajjan and Minister of International Development Marie-Claude Bibeau visit several of them. Officials and military personnel spend several weeks in Africa conducting a technical assessment of each peace operation and holding political discussions with the various actors on the ground.

Public servants then develop four deployment scenarios, each with three options: small, medium, or large. The scenario of a large deployment in Mali is the one favored by all.

Berzins and I are familiar with these scenarios and, after discussions with our counterparts at National Defense, give our green light. Minister Dion and the Minister of National Defense receive a full briefing prior to a meeting on December 1, 2016 with members of the Cabinet Committee on International Affairs.

The day before, at midnight, I prepare Dion's notes for his colleagues. At committee, Minister Dion presents the scenarios and they pass the ramp. We must now inform the Prime Minister. Meanwhile, at the UN, the Office of the Secretary-General prepares for the appointment of a French-speaking Canadian general to head the Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). Everything is ready for a meeting with Trudeau to get his agreement.

Patatras! The Prime Minister's entourage panics. Everything is going too fast, they say to his office. Some advisers want to make sure they understand the different scenarios. Therefore, they prefer to postpone the announcement of participation in a peace operation at the end of January 2017. Finally, after days of discussions between cabinet ministers and the Prime Minister's Office, Thursday, December 15, Trudeau receives Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces, General Jonathan Vance, a two-hour briefing on the various scenarios and the proposal for a deployment in Mali. The Prime Minister is satisfied. He intends to discuss it with the Council of Ministers towards the end of January when the holidays return. At the UN, we are ready to delay the appointment of a Canadian general to head MINUSMA. But January 6, 2017, new twist: the prime minister fired Dion.

I leave the office of new Minister Chrystia Freeland on February 10, 2017. Her chief of staff informs me that the issues I am dealing with - multilateralism, peacekeeping, Africa - are not a priority for her. All his energy is now focused on relations with the United States and the renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement. Reengagement in peace operations is currently in limbo. In fact, until the announcement of Vancouver in November 2017, the Prime Minister's Office plays ping pong with Foreign Affairs and National Defense. Clearly, Trudeau's advisers convinced him to reject the proposed scenarios and to demand new, less ambitious ones.

The announced contribution remains limited. Canada will not play a role in supporting the peace process.

Three reasons explain this reversal: political, financial and security. The Prime Minister and his advisers have lost all political will to engage Canada in resolving a conflict. And the conflicts in which the United Nations is involved are often violent and inextricable. The case of Mali is instructive in this respect. The country is indeed grappling simultaneously with terrorist attacks and a difficult process of national reconciliation.

Secondly, the planned deployment in Mali is expensive. It varies from several hundreds of millions of dollars depending on the options selected. As the government anticipates the increase in the deficit, this new spending places it in an uncomfortable situation.

Finally, the third reason is the risks that this mission represents for future Canadian peacekeepers. The specter of Afghanistan haunts the government and many Canadians. In ten years of presence in Afghanistan, Canada has lost some one hundred and sixty soldiers. The UN mission in Mali is in no way comparable to that of NATO in Afghanistan, but more than a hundred peacekeepers have died since 2014. Trudeau backs off. The risks frighten him. In his mind, there is no question of deploying a contingent of Canadian soldiers. The message is transmitted to the UN, and on March 2 a Belgian general takes command of MINUSMA.

Scenarios of substantial deployments now spread, the Prime Minister is looking for a way out to save face. The Vancouver meeting is fast approaching, and Canada has nothing to offer. Trudeau's councilors are asking officials to propose other avenues that are cheaper and less risky. Over the months, officials provide half a dozen options, all rejected by the Prime Minister's Office.

In late summer 2017, just weeks before the opening of the Vancouver meeting, Foreign Affairs and National Defense officials are increasingly nervous. They are relaunching the Prime Minister's office, which is coming back with an unusual request. He urged officials to no longer focus on deploying to a particular mission, but rather to think about generic participation in UN peace operations: a transport plane; a group of helicopters; a training program. The officials are stunned. For the past year, they have been discussing with their counterparts in the United States, Europe, Africa and the United Nations a proposal to deploy military and police in one or two peace operations. All their interlocutors are preparing for this eventuality. And now the Prime Minister has changed his mind.

In Vancouver, the Prime Minister presents the Canadian re-engagement contribution to peace operations. This contribution is the result of last-minute consultations, made in the emergency even as the conference opens. It is modest and two-pronged. The first component provides funding for targeted programs that can be implemented in Canada or abroad: $ 24 million to modernize peace operations and increase the number of women in missions.

The second part of the contribution deals with the procurement of equipment and the deployment of personnel. It puts at the disposal of the UN a transport plane, a group of helicopters and a rapid reaction force. However, this participation in equipment and personnel is not a firm commitment.

The Prime Minister presents this contribution as an innovative and modern approach to improving peace operations. She is none of that. Canada no longer participates in United Nations operations since the mission between Ethiopia and Eritrea in 2000. And, of course, since that time, the one hundred and twenty-four countries contributing to peacekeepers are not waiting for Canada to innovate and modernize peace operations.

Canada's contribution to peacekeeping announced in Vancouver does not impress anyone. At the UN, the Secretary-General and peacekeepers are disappointed.

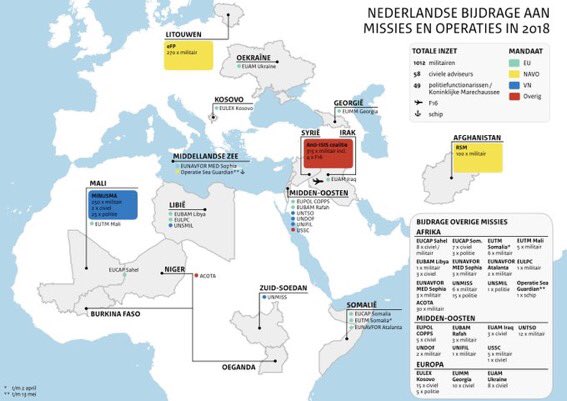

On March 19, 2018, to everyone's surprise, the government announced the deployment of a contingent of peacekeepers in the UN mission in Mali, consisting of a six-helicopter unit and a logistical support group.

The Prime Minister yielded to international pressure and to those who spoke in his office. In the face of some foreign policy decisions, Justin Trudeau knows how to be bold, but most of the time, he is reactive rather than proactive. He hesitates, he procrastinates, he is subject to turnaround. In the case of participation in the mission in Mali, events rushed in March and forced him to act. Several Allied countries with troops in Mali, including Germany, France and the Netherlands, have put strong pressure on Canada to participate in the joint peacekeeping effort in that country. In particular, Germany was looking for a country with helicopters to replace its own on the ground.

In the government, discontent is growing. Many in Foreign Affairs argue that Canada is absent on the international scene when it is due to receive in June the leaders of the G7 countries, some of whom have blue helmet contingents abroad.

The announced contribution remains limited. Canada will not play a role in supporting the peace process. Therefore, it gives up one of its traditional roles, which was to engage in conflict resolution.