Shot, over

Why The Science Behind the UN/IPCC Climate Reports is “Unsettled” – David Yager

Why The Science Behind the UN/IPCC Climate Reports is “Unsettled” – David Yager

When it comes to climate change, the frequently repeated mantra is “The science is settled.” Those who dare raise questions are labelled climate change deniers. Everybody else just agrees with everything and keeps their views to themselves.

Except scientist and author Steven E. Koonin, who begs to differ. The title of his book is

Unsettled – What Climate Science Tells Us, What It Doesn’t, and Why It Matters.

Climate science was again headline news on August 9 after the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued its latest report. Starting with the first report in 1990, the IPCC has concluded climate change is a growing problem with serious consequences. Subsequent reports in 1995, 2001, 2007 and 2013 were accompanied by increasingly stronger language to highlight the enormity of this growing threat.

In the 2021 version, the IPCC chose language that can be fairly described as histrionics. The IPCC’s AR 6 (Assessment Report) media release used descriptive wording you’d normally expect from radical environmental lobby groups pitching certain doom to terrify people into donating money and buying memberships.

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres called AR 6 a “code red for humanity” adding, “The alarm bells are deafening. This report must sound a death knell for coal and fossil fuels, before they destroy our planet.”

Does this sound like science? This is pure alarmist political hyperbole. Taken literally, even the rocks are not safe from the ravages of fossil fuels.

But the IPCC’s public communications are no longer about true climate science, nor have they been for some time. This is one of the key points in

Unsettled, written by physicist/scientist Steven E. Koonin who was the former Undersecretary for Science under President Barack Obama in the US Department of Energy.

Koonin is a serious guy with serious reservations about the IPCC. While never suggesting that carbon dioxide does not trap heat in the atmosphere or that human activity is not a contributor to global warming and climate change, his issues are with the inner workings of the IPCC and the alarmist news coverage of everything related to the weather.

Because to Koonin, there is pure science – the academic process meant to underpin the IPCC’s research – and “The Science,” words used to justify lazy and misleading journalism, preach impending disaster, advocate for unworkable fossil fuel alternatives, and demand that the entire global energy complex be replaced immediately regardless of cost.

Since the IPCC was created in 1988, its ARs have been commonly considered the holy grail of climate modelling. After all, 97% of the scientists involved agree that CO2 emissions from fossil fuels are essentially a thermostat. The higher the CO2, the higher the temperature and more volatile the weather.

Except this isn’t true. The 97% agreement figure has been debunked multiple times in multiple places. But like any skepticism associated with the subject, it was drowned out by the crescendo of voices claiming that the world faces a climate emergency and that anyone who doesn’t agree is an enemy of the future of humanity.

But as a physicist and scientist, Koonin is concerned that many of the fundamental drivers behind public concerns and climate change policy do not have an unquestionable foundation in classic academic science.

So he wrote a book about it. Using the simplest words possible for such a complex subject and numerous graphs and charts that are quite understandable with a little study, Koonin explains where he believes The Science departs from established and accepted scientific methods.

Koonin states that the public communications about the IPCC’s work and the actual state of the world’s climate are “profoundly misleading.” He writes on the inside cover, “…core questions – about the way the climate is responding to our (human) influence and what the impacts will be – remain largely unanswered.”

He began his career building computer models to study atoms and nuclei using the same basic tools as the IPCC uses for its climate models. Before joining the Obama administration, he was a professor at Caltech and later the chief scientist at BP where he focused much of his work on renewable energy. In DC he writes, “I helped guide the government’s investments in energy technologies and climate science.”

But everything changed in 2013 and 2014 when Koonin was asked by the American Physical Society – the professional organization of America physicists – “to ‘stress test’ the state of climate science.” This included examining in detail the different climate modelling methodologies.

Koonin writes that he finished this process “not only surprised but shaken.” The models used insufficient input data to separate natural from human causes. Various climate models contradicted each other and therefore required non-scientific “expert judgement” to achieve the desired outcome. Government and UN pronouncements were so different from the contents of the reports that some climate experts were embarrassed. Koonin added, “the science is insufficient to make useful projections about how the climate will change over the coming decades.”

Wow. You don’t read that every day.

He starts by explaining the difference between climate and the weather, repeating an old saw dating back to 1901 which states, “Climate is what you expect; weather is what you get.” The most important part of the early pages of the book is that weather is not climate, and the highly publicized severe weather events experienced today are not the worst ever, nor are they occurring more frequently.

But thanks to the internet and profound changes in how news is created and distributed, today’s non-stop reporting of all global forest fires, floods and storms leads many to conclude that things are indeed getting worse. And thanks to the IPCC and thirty years of increasingly unquestioned repetition, fossil fuels and growing CO2 emissions are the primary causes.

Koonin indicates that severe weather events have been around for centuries and will be with us for centuries, no matter how successful the world’s attempt to quit using fossil fuels prove to be.

He also illustrates that while the world has indeed warmed 1oC since the start of the industrial revolution, it has not been a straight line. The world warmed steadily from 1910 to 1940, then levelled off until 1970. Warming then resumed. Koonin emphasizes that most of the current focus is on the past fifty years, not the 60 years before that.

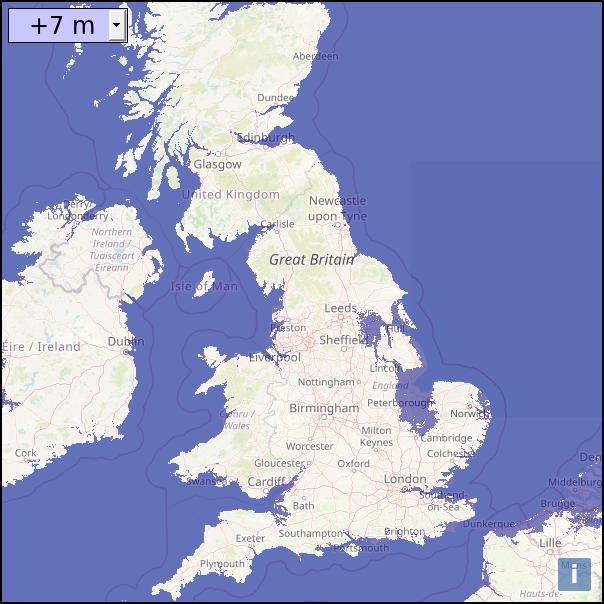

The rate of rise of the oceans has been roughly the same for centuries, about a foot every hundred years. Ocean levels have undergone massive fluctuations in the past, increases and declines completely unrelated to the planet’s growing population and fossil fuel consumption.

Koonin then dives into the how climate models work, making this complex subject understandable. There are wide variations among the different computer programs and methodologies but what bothers the author most is that the models don’t accurately duplicate historical events, even from the 20th century.

Which means something is wrong with the methodology. Koonin’s point is if climate models can’t replicate the past, how can they predict the future? Of the 1910 to 1940 warming period Koonin writes, “…they’re saying that we’ve no idea what causes this failure of the models. They cannot tell us why the climate changed during those decades. And that’s deeply unsettling…”

Another major factor is the impact of clouds and aerosols (airborne particles and chemicals) which reduce warming by the sun. Koonin quoted one researcher who said, “Cloud-aerosol interactions are on the bleeding edge of our comprehension of how the climate system works, and it’s a challenge to model what we don’t understand.”

Another phenomenon of modern climate research is looking backwards; an unpleasant weather event occurs then The Science determines if this was a recurring natural phenomenon or caused by human induced climate change. These are called “attribution studies.”

The IPCC’s 2012 Special Report on Extreme Events concludes, “Even if there were no anthropogenic (man-made) changes in climate, a wide variety of natural weather and climate extremes would still occur.”

The World Meteorological Organization adds, “…any single event, such as a severe tropical cyclone (hurricane or typhoon), cannot be attributed to human-induced climate change, given the current status of scientific understanding.”

Koonin matches modern with historical data. Tornadoes are a good example. Because of modern communications and satellites, even the smallest tornadoes are now recorded. This shows an upward trend since 1950. However, when Koonin sorts them out by size (big enough to be noticed and documented from 1954 to 2014), there is no average increase in higher strength tornadoes and a decline in the most powerful twisters.

On to droughts. Koonin reconstructs severe drops in the flow of the Colorado River dating back to AD 750 using tree rings. Another chart titled “California Drought Severity Index” dating back to 1900 shows multiple droughts in the past 120 years before the recent most recent dry period.

Forest fires? Koonin’s chart shows a steady average decline in the global burned areas since 2003. Human factors like clearing the land for agriculture are a far greater cause of forest fires than climate change.

He even takes the time to brand former Bank of Canada chief and UN climate envoy Mark Carney as a climate alarmist. While still head of the Bank of England in 2014, Carney said the previous winter was the “wettest since the time of King George.” Koonin’s rainfall chart from 2020 back to 1770 indicate that 2014 was hardly an anomaly.

On Carney Koonin wrote, “…it’s surprising that someone with a PhD in economics and experience with the unpredictability of financial markets and economics as a whole doesn’t show a greater respect for the perils of predictions…and more caution in depending upon models.”

Weather related deaths have continued to decline for the past 110 years. “Deaths from wildfires in any decade are too small to be visible on this chart.” Despite warnings about how climate change will cause food shortages, as the population grew by billions in the past 110 years, Koonin graphs how the inflation-corrected price of grain in 2000 was 90% lower than in 1910.

The media regularly repeats the predictions of dire economic consequences from a warming world, but all the climate models – even those with much higher temperatures – show steady economic growth for the rest of the 21st century.

Koonin is highly critical of modern media coverage writing, “…as the age of the internet advances, headlines become more provocative to encourage clicks – even when the article itself didn’t support the provocation…Whatever its noble intentions, news is ultimately a business, one that in this digital era increasingly depends upon eyeballs in the form of clicks and shares. Reporting on the scientific reality that there’s hardly been any long-term change in extreme weather events doesn’t fit the ethos of ‘

If it bleeds it leads’.”

So nowadays almost every reported bad weather event quote somebody who claims that it was either caused or made worse by climate change. No research, no historical context.

After 205 pages of detailed explanation, Koonin switches to commentary. He concluded years ago that the CO2 emission reductions required to meet the agreed-upon temperature ceilings by 2030 and the increasingly repeated chant of

Net Zero by 2050 were impossible.

Besides the enormity of replacing the existing energy infrastructure on a global scale, once people fully understand what the “energy transition” really means to their lifestyle and incomes, voter support tumbles. People don’t understand the degree to which fossil fuels have helped create and support the wealth and comforts of modern society.

Plastics, petrochemicals, fertilizers and the powerful energy sources required for heavy transportation and manufacturing of basic construction materials cannot be replaced with interruptible electricity.

Koonin highlights the recent phenomenon of OECD countries shutting down their carbon intensive industries to appear to be tackling the emissions problem. But voters continue to buy the same products from other countries like China which use low-cost coal as the primary energy source. This is politics and virtue signaling that does not change the chemical composition of the planet’s atmosphere.

While the wealthy west may be able to afford converting to low carbon energy, the developing world cannot and, unless forced, will not.

Therefore, Koonin also puts forward Plan B. If CO2 emissions are proven to be primary cause of warming but the people of the world choose not to replace fossil fuels because of excessive costs and disruption, the author sees two solutions, both expensive and unproven.

The first is Solar Radiation Management – blocking the sun’s radiant heat with materials placed in the upper atmosphere. The other is Carbon Dioxide Removal, which is taking CO2 out of the atmosphere in huge quantities.

As a scientist, Koonin feels the need to explain there are more scientific methods of altering the climate besides fear, sacrifice, taxes, politics and promoting fossil fuel substitutes that don’t work.

When it released AR6, the IPCC knew that declaring fossil fuels will destroy the planet would make headlines and grab eyeballs. But those who actually read the 4,000-page report discovered that the likelihood of very high temperature extremes have been downgraded.

A

Wall Street Journal article on August 11 read, “…the IPCC has dialed back the probability of (without ruling out) more extreme changes in temperature. Such scenarios have been used to justify faster and costlier action to ban or limit fossil fuels.”

Which underpins Koonin’s points. There’s true climate science – complex and under continuous development – and there’s The Science, which spreads fear measured in decibels, not degrees Celsius.

Is Koonin right? He admits he could be wrong. Which is why he wants to fund research into blocking the sun’s heat with a giant chemical umbrella.

Is what you read about climate change in the news right? Absolutely not.

Why The Science Behind the UN/IPCC Climate Reports is “Unsettled” - David Yager - Energy News for the Canadian Oil & Gas Industry | EnergyNow.ca