As mentioned in two previous reports—a long one, and a short one—some things are known, and many are not, about the horrific crash this past weekend outside Addis Ababa, in which all 157 people aboard a new-model Ethiopian Airlines 737 Max were killed.

One thing that’s known: This is the second crash of this kind of plane within the past five months, following the Lion Air crash in Indonesia last year.

One thing that’s not known: whether the two crashes are related, which would suggest a disastrous system flaw with the 737 Max and its software.

Just this afternoon—minutes ago as I type, four days after the Ethiopian crash— aviation authorities in the United States and Canada joined their counterparts in Europe and Asia in grounding the 737 Max fleet. This is until more is known about whether the crashes are connected and whether there is something systematically wrong with the plane.

...

What will happen with the 737 Max? At this point, again, no one knows—or has said publicly. As a practical matter, grounding all Boeing 737s would have an enormous effect on world air travel, since they’re the most popular airliners on Earth, with a production run of well over 10,000. Although more than 5,000 orders have been placed for the 737 Max series, only a few hundred of them have gone into service, fewer than 100 with U.S. carriers. Most airlines can cancel those Max flights without fundamentally disrupting their service.

...

Boeing, like Airbus, has earned trust for decades’ worth of safe decisions. The FAA, like most of its counterparts, has earned similar trust for its safety-mindedness—despite endless grievances from pilots, airlines, and aircraft companies about aspects of FAA bureaucracy. If either Boeing or the FAA is making the wrong choices now, the airline-safety culture will certainly recover—but their reputation and credibility might not, for a very long time.

While the fundamentals remain unknown, here are some relevant primary documents. They come from an underpublicized but extremely valuable part of the aviation-safety culture. This is a program called ASRS, or Aviation Safety Reporting System, which has been run by NASA since the 1970s. That it is run by NASA—and not the regulator-bosses at the FAA—is a fundamental virtue of this system. Its motto is “Confidential. Voluntary. Nonpunitive.”

The ASRS system is based on the idea that anyone involved in aviation—pilots, controllers, ground staff, anyone—can file a report of situations that seemed worrisome, in confidence that the information will not be used against them. Pilots are conditioned to treat the FAA warily, and to make no admissions against interest that might be used again them. What if I confess that I violated an altitude clearance or busted a no-fly zone, and they take away my certificate? But they’ve learned to trust NASA in handling this information and using it to point out emerging safety problems. I’ve filed half a dozen ASRS reports over the years, when I’ve made a mistake or seen someone else doing so.

...

Below are all of the reports I could find that are related to possible runaway-trim problems with the new 737 Max. As a reminder, that is the presumed cause of the Indonesian Lion Air crash, and possibly a factor in the accident in Ethiopia. I won’t annotate or parse them, but I offer them as the documentary supplement to what you’ll read about in the papers.

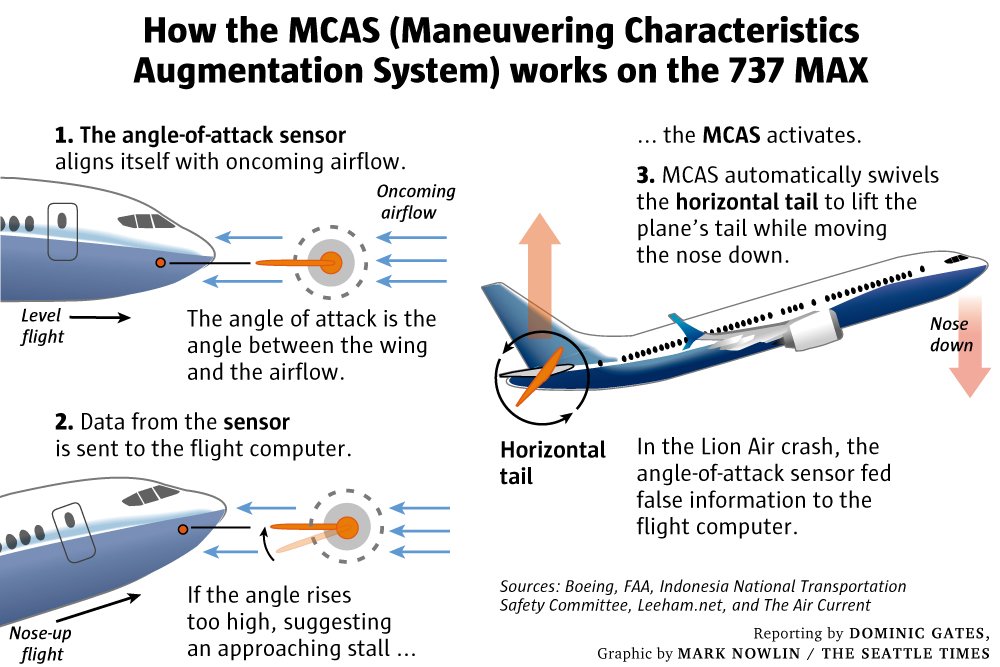

The first four reports involve the aspect of the 737 Max software most in the news: its MCAS program that automatically lowers the nose of the plane, even if the pilot does not want the plane to descend. In these cases, it is worth noting, these U.S.-carrier pilots disabled or overrode automated systems and took control of the plane themselves. Obviously none of these flights crashed.

Here we go. Most readers will want to skip to “Narrative” and “Synopsis,” but I have left in all the other information just for the record:

[a number of ASRS reported incidents related directly to 737 MAX trim runaway situations]

...

That’s what is on the record, from U.S. pilots, about this plane. If I’ve missed any relevant 737 Max reports among the many thousands in the ASRS database, I assume someone will let me know about them. We’ll see where the evidence leads.

Here is another highly relevant offering for the day. It comes from J. Mac McClellan, a longtime writer and editor in the flying world, at the Air Facts site. He argues that Boeing may have been assuming that pilots would note any pitch anomaly, and override it if it occurred (as appears to have happened in the incidents involving U.S.-carrier pilots that were reported in ASRS). His whole article, about how airlines manage the complexities of automated and human flight guidance, is worth reading.

In the article, called “

Can Boeing Trust Pilots?,” McClellan writes:

What’s critical to the current, mostly uninformed discussion is that the 737 MAX system is not triply redundant. In other words, it can be expected to fail more frequently than one in a billion flights, which is the certification standard for flight critical systems and structures.

What Boeing is doing is using the age-old concept of using the human pilots as a critical element of the system ... In all airplanes I know of, the recovery is—including the 737 MAX—to shut off the system using buttons on the control wheel then a switch, or sometimes circuit breaker to make a positive disconnect.

Though the pitch system in the MAX is somewhat new, the pilot actions after a failure are exactly the same as would be for a runaway trim in any 737 built since the 1960s. As pilots we really don’t need to know why the trim is running away, but we must know, and practice, how to disable it.

Boeing is now faced with the difficult task of explaining to the media why pilots must know how to intervene after a system failure. And also to explain that airplanes have been built and certified this way for many decades. Pilots have been the last line of defense when things go wrong

...

But airline accidents have become so rare I’m not sure what is still acceptable to the flying public. When Boeing says truthfully and accurately that pilots need only do what they have been trained to do for decades when a system fails, is that enough to satisfy the flying public and the media frenzy?